Vietnam North to South – Day 12: North of Saigon

Today was a real adventure, as my dad and I decided to split off from the main group and head to Saigon early instead of spending the day in Nha Tranh. Every part of the journey was an experience. Riding to the airport, we found that local taxi drivers love to play karaoke on their displays. While they likely don’t sing along (our driver, at the very least, did not), the text running at the bottom of the screen seems rather distracting. As do the music videos that accompany the songs, with cameramen focussing on the cleavage of female singers.

The only

way we were able to book our flight with VietJet was by ordering seats in a

category called “Sky Boss.” I did not imagine this would grant us particular

privileges besides getting to use the VietJet Lounge and boarding the aeroplane

first. However, my expectations were turned upside down when we were whisked to

the bus in our own bus, after which the crew gave us an almost uncomfortable

amount of attention throughout the entire trip. They even made sure to thank us

personally for choosing the airline right before we landed. I imagine people do

not fly “Sky Boss” very often, as I noticed that the sign for the middle seat

above our heads had been crossed out with a marker.

This was

the first time I have flown VietJet, and its culture seems rather different

from the state-owned Vietnam Airlines. For one, female flight attendants on the

latter wear turquoise áo dài, a type of long split tunic worn over trousers,

with the chief attendant clad in yellow. They also tie their hair in buns. In

contrast, VietJet’s flight attendants wear red shirts, beige shorts, and beige

caps, which despite VietJet’s private ownership makes them look like Young

Pioneers. This impression is further reinforced by the fact that while the

flight attendants of Vietnam Airlines bow before landing, VietJet’s flight

attendants make a crisp salute.

While I’m

on this subject, I cannot help but note that VietJet’s departure and arrival

playlists are pure gold, especially in comparison with the sappy tracks on

Vietnam Airlines. The one song that sticks out the most is Trọng Tấn’s

rendition of Tiếng Hát Từ Thành Phố Mang Tên Bác, an ecstatic nationalist piece

on Ho Chi Minh and Ho Chi Minh City.

Our

adventure continued at Tan Son Nhat Airport, where we were able – after

overcoming some linguistic barriers – to arrange for a ride to Tây Ninh with a

stop by the Củ Chi Tunnels. It turned out that our driver not only spoke zero

English, but had also never been to either place and did not excel at reading

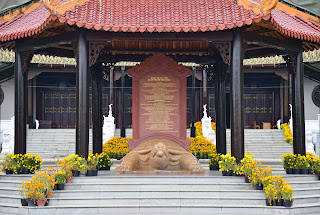

maps. Nearing the tunnels, he stopped prematurely at the Vietnamese Memorial

Complex, a massive temple honouring the killed freedom fighters. Excepting the

gardener, it was completely deserted. After walking around for a while and

bumping into a guard by the southern entrance to the whole Củ Chi Tunnels

compound, we determined we needed to drive a little farther north. Nevertheless,

arriving at the complex was quite a happy accident, as it is a monumental

place.

The Củ Chi Tunnels

can only be visited in the company of a guide, but visitors are first funnelled

to an outdoor cinema where they watch a documentary about the Viet Cong. A

little propagandistic in its language, it speaks of “American devils” shooting

at everything from women and children to chicken, ducks, and Buddha statues. Of

course, it also praises the brave Vietnamese heroes and recounts the number of

Americans killed by the most efficient among them.

Following

the film, a guide stopped by to pick up our group of independently arrived

individuals and families. He showed us around the Củ Chi tourist route and led

us through some of the tunnels, which have been artificially expanded for us

bulkier overseas visitors. Still, they felt tiny and deoxygenated, and I only

visited two before telling myself that once you’ve seen one tunnel you’ve seen

them all. I did not dare to go down the original-sized tunnel, where most men

can only fit by raising their arms to decrease the breadth of their shoulders.

From Củ Chi

we continued for a little over an hour to the city of Tây Ninh. The place was a

complete contrast to any city we have seen on this trip: it mostly comprises two-story

houses, which do not quite fit with the city’s broad boulevards. Practically

none of the road signs or street advertisements are in English, and no one

seems to speak English either. Indeed, both children and adults greet strangers

with enthusiastic hellos; the more educated among them even throw in a quick

“Where are you from?” Strangely, Tây Ninh is filled with Apple stores, sweet

tea vendors, and motorcycle dealerships, and the more frequented areas are

patrolled by sellers of lottery tickets. The winning combinations seem to be

displayed on boards along the roads, which often preside over whole cemeteries

of discarded tickets.

We checked

into our hotel with minimal difficulty, though the staff at the front desk

needed to use a translation app on their phone to communicate in English. Nevertheless,

we managed to call a taxi to the Tây Ninh Holy See, the centre of the Cao Dai.

Founded in 1926, Caodaism is a syncretic religion fusing elements of Buddhism,

Taoism, Confucianism, and Christianity. It venerates a disparate host of

spiritual leaders and philosophers, including the Buddha, Laozi, Confucius,

Jesus, and Jiang Ziya. Behind the entrance of churches one can usually find a

painting of the “three saints” of Caodaism – Victor Hugo, Sun Yat Sen, and Trạng

Trình Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm – writing the phrase “God and Humanity; Love and Justice”

in French and Chinese.

The

followers of Caodaism traditionally wear white robes for worship, with the men

often donning black turban-like hats. The priests wear cloaks of yellow, blue,

or red, depending on their affinity for either Buddhism, Taoism, or

Confucianism. These colours are also heavily present on the facades of Cao Dai

churches, as well as on flags and decorations. We saw many followers and even

some priests gather for the six o’clock ceremony, during which the entire area

around the church was sealed off.

The Holy See, also called the Great Divine Temple, is spectacular. Brightly coloured and decorated all around with the left eye of God, it features statues of saints on the walls and animals by the side entrances. With its church-like layout and curved roofs, it blends European and Asian influences, all the while contributing its own features like a giant globe on the central tower. Inside, dragons wrap around pink pillars, and men clad in white guide tourists to make sure they do not disturb prayers and stay on the designated pathways. Incidentally, the four other tourists were the only other Europeans we saw in Tây Ninh all day.

Comments

Post a Comment