The Baltics – Day 6: Vilnius and Kernavė

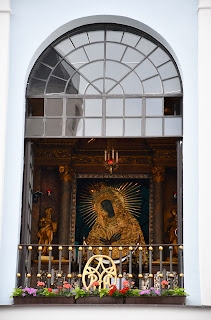

This morning was the first cloudy morning during my entire trip, and I was very thankful for it. While it meant my pictures would not be full of beautiful azure skies, it also stopped my bouncing from shade to shade like a desiccating frog. My first stop today was the Gate of Dawn, which houses a prominent icon of the Virgin Mary in a chapel facing the inner part of the city. When locals walk through it, they often turn around and cross themselves, sometimes adding a short prayer. Right in the vicinity are the Church of Saint Theresa and the colourful Orthodox Church of the Holy Spirit, and farther along the same road one can see the imposing baroque-era Church of Saint Casimir and the city’s neoclassical town hall.

Walking north, I arrived at Vilnius Cathedral. The

building is altogether quite unusual: with columns on three sides, it looks

almost like a Greek temple, and its impressive bell tower stands unconnected to

the rest of the building. I saw nothing too remarkable inside the cathedral

except for a very ornate chapel on the far right. After that, I climbed the

nearby Gediminas Hill, on the top of which stands an octagonal brick tower and

the ruins of a castle from the early fifteenth century. Fortifications on the

hill date to the reign of Gediminas, Grand Duke of Lithuania, who is said to

have founded the city of Vilnius.

Since it was still too early for most of the churches

and museums to open, I continued my loop around the centre of old Vilnius.

Passing by the red brick Church of Saint Anne and the Church of Saint Francis

of Assisi, I crossed the river and somehow wound up in a different world: with

Tibetan signs, prayer flags, and graffiti, the park Tibeto skveras seemed like

a fata morgana. Lithuania is an outspoken advocate for countries and cultures threatened

by the PRC, which may also be part of the reason why I saw no Chinese tourists

in the city. Just a few metres south of this park stands the Angel of Užupis, and

across the river looms Bastion Hill with its semicircle of impressively thick

walls.

I spent the rest of the morning at the Palace of the

Grand Dukes of Lithuania, which houses a very extensive museum. The building

was plundered and greatly damaged by the Muscovites in 1655, after which it

remained in a state of disrepair for another one hundred and fifty years, being

demolished in 1801 under Russian rule. As recently as the year 2000 was a law

passed to reconstruct the palace, and the new building was opened to the public

in 2013.

I found the exhibitions illuminating for several

reasons. Firstly, I knew very little about the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth,

and receiving the unashamedly pro-Lithuanian perspective gave me some

background. According to this account, the major cause of Poland-Lithuania’s

downfall was national and political disunity. The Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648,

for example, began when the Sejm cancelled Władysław IV Vasa’s planned attack

on the Ottoman Empire. This greatly disappointed the Ukrainian Cossacks, who appealed

to the Tsardom of Muscovy for support. Further conflicts between the king and

the nobility facilitated Sweden’s invasion of 1701, and generally tended to

prevent the king from doing almost anything.

Secondly, the museum provided an interesting lesson in

post-Soviet historiography. For example, the inhabitants of Kievan Rus were

termed “Rus’ians” to prevent readers from drawing an equivalency between them

and modern Russians. The issue of terminology is highly significant, as modern Russian

polemicists trace a direct line from the Kievan Rus to justify Russia’s claims

to Ukraine, Belarus, and other areas in sovereign countries. Similarly, the

museum always referred to the Tsardom of Muscovy rather than the Tsardom of

Russia, only reserving the term for the Russian Empire, proclaimed in 1721.

Some of the things I learned, though, were just fun

history titbits. For instance, Lithuania was the last pagan country in Europe,

only accepting Christianity in 1387. For comparison, the reformer and

proto-protestant Jan Hus was born in 1369, and the Crusaders were permanently booted

from the Holy Lands as early as 1291. I also learned that the ruler who

initiated Lithuania’s Christianisation was Jogaila, the King of Poland and

Grand Duke of Lithuania. By marrying the Poland’s Queen Jadwiga, he brought

about the personal union of Poland and Lithuania, and he is the namesake of the

influential Jagiellonian Dynasty.

I left the museum a little later than I had expected,

and too late to make it on time to the first stop of the bus to Kernavė. Fortunately,

Google Maps figured out a way for me to intercept the bus on its journey out of

the city – even giving me enough time to buy a wrap at the last stop. The downside of catching the bus this

late was that by the time I ascended, all the seats were taken, and I had to

stand awkwardly on the steps for the first leg of the journey, as the grannies

in front of me were too engrossed in their conversation to move farther back.

This was

still nothing in comparison to my return journey though. Having seen what there

is to see in Kernavė – a few big mounds that were once the site of Lithuania’s

first capital – I made my way over to the Kernavė bus station to wait for the

bus back to Vilnius. I had planned my trip to give myself around an hour in Kernavė,

and this specific combination of connections was the only one that would keep

me from having to stay for around three hours.

My disappointment was great, therefore, when – after

it had begun to rain – I saw my bus speed past the stop without a single care

in the world. I imagine it must have picked up people closer to the centre of

the city, as this is where passengers requested it to stop on my way to Kernavė,

but I did not expect it to bypass a whole roofed building with a big sign and

timetables in the front.

Looking into Google Maps again, I found that a bus was

supposed to leave from another nearby town in around an hour and a half. With

the rain pouring down, I made a five-kilometre trek to Miežionys, where

I once again stationed myself at the bus stop and waited for the bus to arrive.

Although the rain had mostly stopped as I was walking, it returned with a fury

several times throughout this wait. The pessimist in me cursed Lithuania, while

the optimist rejoiced in the learning experience: I found out how to squat to

keep my shoes from getting wet, as they are always the most difficult to dry.

With my hour of waiting over and the bus nowhere in sight, I

wrote to my Lithuanian friend Diana to ask for advice. Unfortunately, she does

not drive, and all her friends were still at work, but using a local transport

app, she found that another bus was supposed to leave from the bus stop

opposite from mine in another hour. I was not very optimistic about this

prospect, but after failing to procure an Uber, I figured this was the best

chance I had. Several more downpours later, the third time was the charm.

I kept Diana apprised of the situation throughout this

series of events, baffling her with my reports on the state of her country’s

public transport. The cherry on top was when the driver made an impromptu stop

and, without picking anyone up, went outside to have a smoke. Diana said she

never experienced anything like it.

I was quite hungry when I returned to Vilnius after six, but

I resolved to see a bit more of the city before visiting a Georgian restaurant

I have had my eye on. Walking past Saint Casimir’s Church again, I got all the

way to Vilnius Cathedral before taking the bus to the Church of Saints Peter

and Paul in the eastern part of the historic centre. When I got there, however,

I found that the church stands at a busy intersection and is blocked by

barricades. Finally, I took the bus back straight to the Georgian restaurant

and had a very filling khachapuri.

Comments

Post a Comment